There have been some strange and contradictory economic data released recently. The following post examines some of these anomalies and discusses the implications for the market.

Politically-Charged September Employment Report

First, let me state that I do not plan to use this forum to express my own political views or agenda. In addition, let me also stress that I do not believe in conspiracy theories, even those espoused by former General Electric executive Jack Welch:

"Unbelievable jobs numbers..these Chicago guys will do anything..can't debate so change numbers."

I do not believe the Obama administration influenced the latest employment report in any way, but the surprising and fortuitous decline in the unemployment rate from 8.1% in August to 7.8% in September has generated a lot of talk in the past two weeks. As a result, I decided to take a closer look at the data for the sole purpose of understanding the accuracy of the employment surveys and the resulting market implications.

Before digging into the numbers, a little background would be helpful. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS):

"The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) has two monthly surveys that measure employment levels and trends: the Current Population Survey (CPS), also known as the household survey, and the Current Employment Statistics (CES) survey, also known as the payroll or establishment survey.

Employment estimates from both the household and payroll surveys are published in the Employment Situation news release each month. These estimates differ because the surveys have distinct definitions of employment and distinct survey and estimation methods."

The CES or payroll survey (which is used to generate the monthly non-farm payroll number) is generally considered to be a much more accurate and reliable employment benchmark than the CPS or household survey (which is used to calculate the unemployment rate). That is why the investment community focuses on the payroll statistics and the general public (and the media) typically concentrate on the unemployment rate.

The household survey sample size is "approximately 60,000 households," while the payroll survey sample size is much larger: "about 141,000 business and government agencies covering approximately 486,000 establishments."

The payroll survey reported an increase in non-farm payroll (NFP) of 114,000 jobs in September, which was generally consistent with my NFP model forecast, at least after adjusting for the recent model bias. The surprise came from the household survey, which reported an increase of 873,000 jobs in September, which was over seven times the non-farm payroll estimate. That is why the reported unemployment rate dropped from 8.1% to 7.8%.

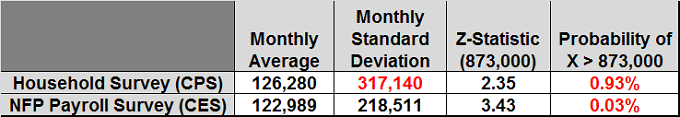

Looking at one month of data does not provide sufficient context, so I analyzed the monthly employment data for both BLS surveys from January 1969 to September 2012 - over 43 years of data and over 500 monthly observations. The results are presented in Figure 1 below.

As you would expect, the monthly averages are very similar: 126K for the household survey and 123K for the payroll survey. Now look at the monthly standard deviation for both surveys. The monthly standard deviation (variation from the mean) of the household survey data is almost 50% higher than the standard deviation of the payroll survey data. This supports my earlier statement that the payroll survey is more reliable and more accurate than the household survey.

We can use the historical data to analyze the probability that the economy really did add 873,000 (or more) jobs in September. The Z-statistic represents the difference between the reported value of 873,000 jobs and the monthly average, divided by the monthly standard deviation. The resulting Z-statistics are 2.35 and 3.43 for the household and payroll surveys, respectively.

Assuming a normal distribution, the probability of a single observation exceeding 873,000 is less than one percent. Based on the payroll survey mean and standard deviation, the probability of the economy adding 873,000 or more jobs in a given month is only 0.03%.

If you look at the actual historical data, there was only one month (in 43+ years) when the payroll survey reported a net gain of over 873,000 jobs (and that observation occurred one month after a NFP number that was an outlier on the low side). The household survey only reported four instances (in 43+ years) of monthly employment growth in excess of 873,000 jobs. These results are generally consistent with the calculated probabilities in the table above.

So, did the economy really add 873,000 jobs in the last month? No. How confident am I in that statement? Somewhere between 99.07% and 99.97%.

Was the household survey report of 873,000 new jobs an elaborate conspiracy to get Obama re-elected? No, it was a simple case of a flawed survey methodology - after all, this is the government we are talking about.

Does that mean that the unemployment rate is not really 7.8% No, it does not. While I am confident that the economy did not add 873,000 jobs in the past month, there is no reason to believe that the 7.8% employment rate reported this month is any more or less accurate than the 8.1% rate reported last month. However, given the above analysis, it is extremely unlikely that the unemployment rate actually declined by 0.3% in September.

Conclusion

The key question for the market and for the overall health of the economy is how many new jobs were actually added in the past month; the NFP value of 114,000 is currently the best available estimate. In other words, there has been no significant change in the employment environment. The economy is still weak and employment growth is still anemic.

Feedback

Your comments, feedback, and questions are always welcome and appreciated. Please use the comment section at the bottom of this page or send me an email.

Do you have any questions about the material? What topics would you like to see in the future?

Referrals

If you found the information on www.TraderEdge.Net helpful, please pass along the link to your friends and colleagues or share the link with your social or professional networks.

The "Share / Save" button below contains links to all major social and professional networks. If you do not see your network listed, use the down-arrow to access the entire list of networking sites.

Thank you for your support.

Brian Johnson

Copyright 2012 - Trading Insights, LLC - All Rights Reserved.

Fascinating, but only one comment– you analyzed data going all the way back to 1969, when the population and labor force were much smaller than they are today. Thus, the data are not comparable. As the population increases, then larger absolute shifts in the Household survey become more likely. To adjust for the size of the labor force, you should take the change as a percentage of the labor force– which just happens to be the percentage rate! Not only more accurate, but more straightforward and simpler. What is the probability the unemployment rate will drop by 0.3 percent any given period?

Tony,

Thanks for your feedback and for your excellent suggestion regarding the employment data. I agree that it would be more appropriate to compare the net change in jobs as a percentage of the labor force, which would adjust for the growing size of the labor force over time. The resulting statistical comparison would then be valid over a number of years.

However, that is not the same as evaluating the month to month change in the employment rate, which also includes the monthly change in the size of the labor force in the denominator, which is not what I was trying to capture in the article.

Per your suggestion, I went back to the historical data and calculated the net number of new jobs created each month as a percentage of the size of the labor force. According to the household survey, there were 873,000 new jobs created in September 2012, which represented 0.565% of the labor force.

Using the new percentage calculations for the entire historical data set, the resulting Z-scores for the household and employer surveys were 1.73 and 2.45, respectively. Assuming a normal distribution, the probability of adding more than 0.565% net new jobs as a percentage of the labor force in a given month were 4.2% based on the household survey and 0.70% based on the employer survey.

In addition to the Z-score, I also counted the number of times the household survey reported a net job change in excess of 0.565% in a given month. Only 3.44% of the months generated net job gains in excess of 0.565% of the labor force.

I did the same calculation for the employer survey. Only 0.70% of the months generated a net increase in Non-farm payroll in excess of 0.565% of the labor force.

As you would expect, these percentages were higher than the values reported in the article. Using net job gains as a percentage of the labor force is more appropriate. The percentages in the article were too low.

Nevertheless, I come to the same conclusion. The odds are very low that the economy actually added 0.565% new jobs in September, expressed as a percentage of the labor force.

Tony, thanks again for your feedback and for your interest in Trader Edge.

Regards,

Brian Johnson